It’s a sort of twilight in this room. People are sitting on folding chairs or the floor, leaning against a wall or holding their knees in the middle of the room, sitting alone or in small groups. Some of the children are restless, two of them are lying on their fronts, heads held in their hands. A man has his eyes closed, resting his head against the wall. One or two people lift up their phones. A young couple walk in and sit in the middle of the room. He has a ginger beard and a top-knot. They snuggle closely together. One woman sits cross-legged, her eyes closed, her fingers pressed together in her lap and pointing. Another woman is lying looking up at the ceiling while across the room a third is also lying on her back although her hands are wafting in conductor’s gestures in time to the music.

The music. That’s what drew me here. It floated across several rooms and I wondered why there was music playing in a normally-hushed art gallery. As I came closer, I could distinguish the sound of a female voice and an organ playing. It sounded live. There was a detailed panel on the wall beside the entrance to the room and I read enough to realise that this was an installation, that the paintings normally on display here had been removed and that it involved the performance of a single Italian song all day during the five weeks of the installation.

Now I find myself sitting on one of the folding chairs, wondering and listening.

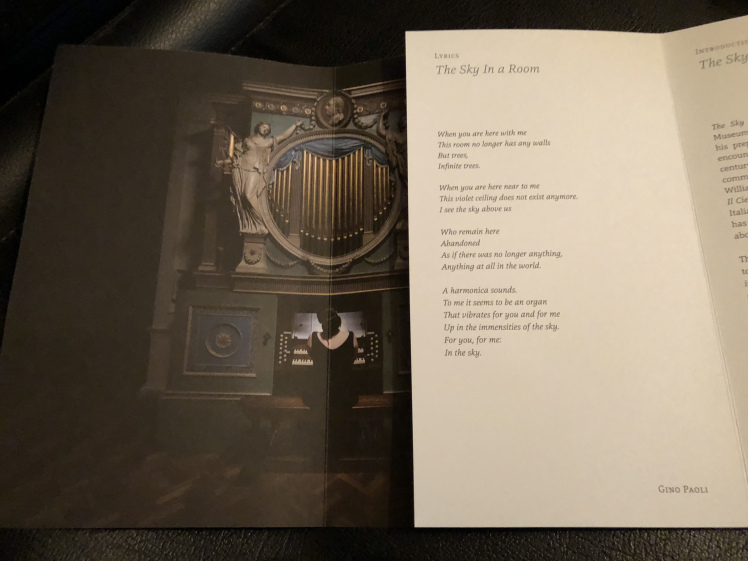

What I can see is this: near one end of a gallery room which has been stripped of its usual artworks is a free-standing false wall in front of which is an ornate organ. It’s painted a sort of turquoise with panels of blue and the white marble of classical frieze figures surrounding a circle cut out to expose the copper of the central pipes. Other pipes are exposed on the left and right. It makes me think a section of an elegant Georgian drawing room has been lifted out and deposited in this room in Cardiff.

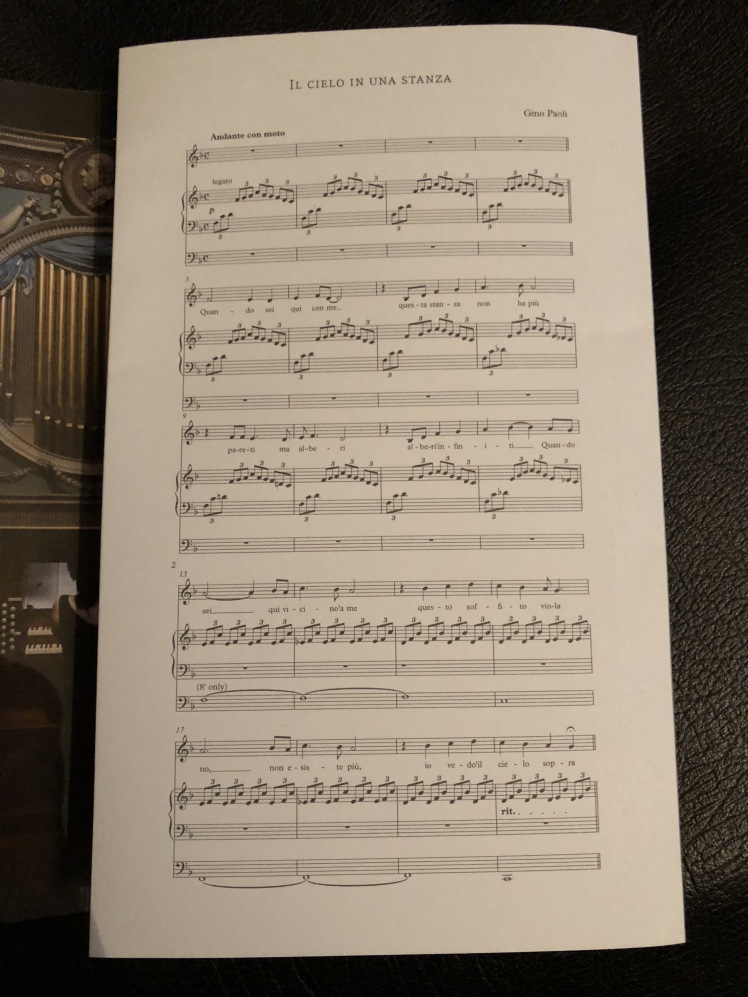

A woman in a formal evening dress is sitting on a bench with her back to us, playing the organ and singing. She moves to the left and right to pull out stops or to reach pedals and sometimes rests one hand on the bench. She never stops playing. She’s singing in Italian a melody that is plaintive and haunting. It’s difficult to tell if it’s an old or a new song. It soon becomes apparent that she won’t pause between ending and starting again.

Then after a while, a bearded young man in a dinner jacket walks into the room and stands beside her, his eyes cast downwards, in his hands a musical score. The woman organist finishes the song, picks up her score and gets up from the bench which he then sits on and opens his copy of the score. I’m not sure whether or not I should applaud the woman who’s leaving. Nobody else claps so I settle for a half-smile as she walks past me.

For a little while, I’m unsure if the new organist is playing the same song or a different one. It sounds different in his voice and his playing. Gradually the melody snakes around my memory of it and I remember the changes, the crescendos and pick out some of the Italian words.

A few people are getting up and leaving the gallery. Most seem transfixed. I look around at the walls papered with rich blue wallpaper. At least I think it’s blue but the light is very low and I can’t really tell the colour nor detect any sign of staining or discolouring where the paintings normally are. There’s light on the organ itself and some straining through glass skylights high above. At the opposite end of the room to the organ, some of the brightness of the neighbouring gallery spills in. Four glass cases at either end of the room are empty.

I think about the performers and wonder how hard it must be on their voices, how stiff their fingers must get and how uncomfortable it must be to sit on a wooden bench so long. I wonder too if they become bored with singing the song. In the time I’ve been here I must have heard it twenty times. What must it be like to hear and sing it hundreds of times? They’re an exhibit too. People walk slowly around the organ, peering at it and the performer as they do so. I wonder too why an artist has caused us all to sit here in Cardiff to listen, look and think these things. I’m glad they have.

I leave the gallery for a coffee and a sandwich but even as I get up to go I’ve decided to return. I pick up the leaflet which is beautiful in itself and read about the project. It’s an installation by Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson. Visiting the National Museum in Cardiff as part of the Artes Mundi scheme, the gallery of eighteenth century paintings which normally hang in that particular room along with the sight of the eighteenth century chamber organ somehow reminded him of a late 1950s Italian pop song, ‘Il Cielo in Una Stanza.’ Four years later he brought room, organ and song together in the installation which was captivating me. Over the course of five weeks, nine organists take it in turns to play and sing the song in this unusual environment.

When I go back, the room is full of different people listening. A woman is lying on her back, her blue cycle helmet and coat beside her matching the blue paint on the organ. Two young girls sit against the wall next to me, their mothers (I assume) away from the wall but nearby. The youngest girl taps the floor between me and her and smiles conspiratorially at me. Her mother starts sliding inch by inch towards her. We’re all chuckling silently. A man opposite leans his head back against the wall, his eyes closed. A young woman is scribbling quickly in a notebook. Like me.

The first organist I heard is playing again. This song I’d never heard before today now feels as familiar as one of my old favourites. I find myself waiting for my favourite moments: a certain crescendo, the way the singer emphasises a particular word, the beginning, the end.

It must be coming towards the end. Instead of another organist, a museum attendant stands next to the performer who looks up at her. The attendant smiles and nods, obviously signifying that she can finish. When the organist gets up, picks up her score and walks away from her bench, you can tell that we’re all wondering whether or not to clap. We do.

A little later, I’m browsing in the museum shop when I realise that the last organist is about to walk past me. I tell her how much I enjoyed it and ask if she ever gets bored singing the song.

‘No,’ she says. ‘It’s very strange. Last Saturday they decided to shut the museum at four so I only got to do the first twenty minutes of my last hour and then I was fed up with it. For some reason when you do the full hour it’s out of your system, but it was like my body said ‘you’ve only done 20 minutes’ and it stayed with me. It was very odd.’

The whole thing is strange I say. She agrees. ‘Strange and amazing. I’m so glad I did it.’

Later still I spoke to another of the organists, Callum Thomson, on Twitter. He told me that ‘physically it was fine – I kept it interesting by slightly varying the tempo and dynamics each time, and giving each repetition a different character in my head (exuberant, melancholy, weird…). Doubt the listeners will have noticed though! Was honestly never bored.’

It was entirely by chance that I got to see this strange and beautiful work. I’m glad I did. In the accompanying leaflet Ragnar Kjartansson says the song is about transformation of space and that’s what he’s achieved in a room in the National Museum of Wales: an antique organ is taken out of place and given new life, a room has been transformed, a song has been transformed and everyone who’s experienced it has been transformed too.

When you are here with me

This room no longer has any walls

But trees,

Infinite trees.

Stunning.

It really was. I’m so glad I saw it.