This is from 2009 and first appeared in a magazine called ‘the Raconteur.’

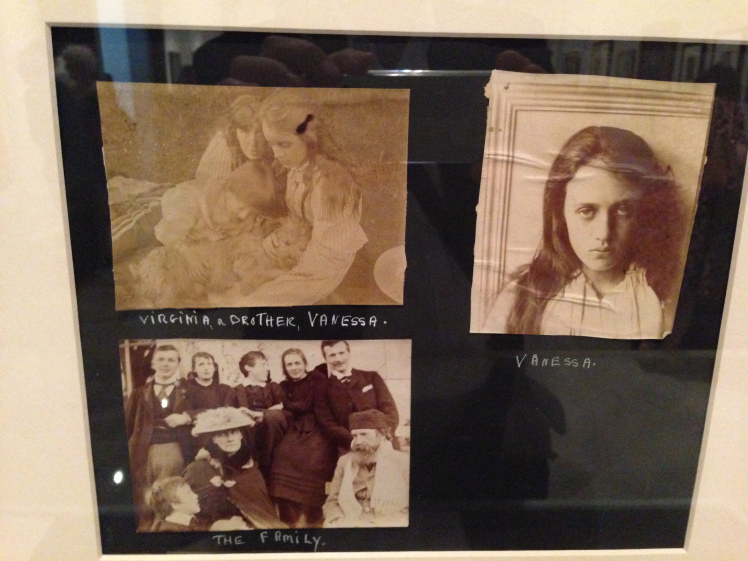

I heard Virginia Woolf’s voice for the first time recently. There’s only one recording of her: it lasts about seven minutes and comes from a 1937 BBC talk; you can find it easily on the internet.

I’d never heard her before, but there she is, delivering playful views on the errant behaviour of words in a surprising voice – not quite as cut-glass as I’d expected (apart from that tell-tale, aristocratic-English rolling of the ‘r’s) but instead approachable, droll and modern.

But then Virginia Woolf is a surprise. You have to push past an offputting reputation that caricatures her as a snob, an elitist obsessed only with a particular Bohemian strand of upper-class Englishness. But if you overcome that, you will find a writer who – like the crackling recording of her voice – speaks vividly across the generations and class divides. And she does so in a still-sparkling style that will make you gasp with admiration.

For in her best, later works what she produced was nothing less than poetry in the form of novels; stories with characters and plots but drenched in imagery and written in rich, impressionistic prose.

It wasn’t always a given that this was what Woolf would produce. The truth is I can’t think of another novelist who has so comprehensively transformed their writing style. If you need proof of that transformation you need look no further than the early ‘Night and Day’.

It would be wrong to think of it as a bad novel; it’s not. On its own terms it’s successful and enjoyable. But its tale of pampered and not-so-pampered upper-class Bohemians, some of whom are forced to work for a living belongs to a vanished time. It’s a nineteenth century novel from a writer whose real worth lies in the way she helped shape our view of the twentieth. Indeed so old-fashioned is the world it portrays of visiting-cards and outraged fathers, canes and gloves, that it’s a big shock when a telephone rings.

What’s more Woolf is only beginning to work out how to convey the emotional and psychological reality that she came to portray so accurately later. Truth be told that aspect of it is a bit clunky: all too often she spells out at great length what’s going on in the minds of her characters.

You can’t criticise someone for not writing masterpieces from the very beginning of their career though and ‘Night and Day’ has plenty to recommend it. All the Woolf elements are there: the notion of family simultaneously bringing freedom, safety and enslavement; the observation that bohemians may be superficially liberated but in fact are as conventional as anyone else and the biggest of all Virginia Woolf themes: the impossibility of true communication at the same time as the vital necessity of trying.

‘All crepuscular’

So how did she move from writing something that reads like an imitation of Henry James to something truly new and truly lasting? She wrote in her diary as she planned ‘Jacob’s Room’, the novel that marked the start of her transformation,

Suppose one thing should open out of another and yet keep form and speed, and enclose everything, everything? For I figure that the approach will be entirely different this time: no scaffolding; scarcely a brick to be seen, all crepuscular, but the heat, the passion, humour, everything as bright as fire in the mist.

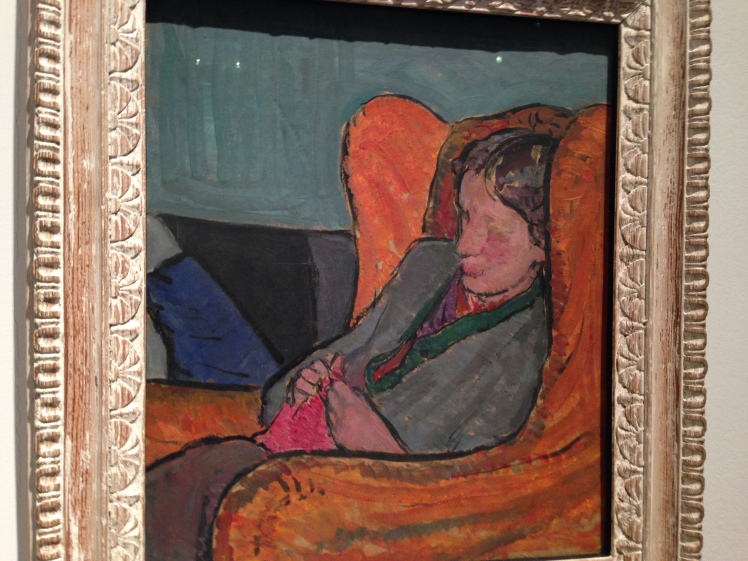

It’s worth always remembering this paragraph when you read Virginia Woolf’s later novels because it forms a kind of style manifesto. What she has learned by the time she writes ‘Mrs Dalloway’ and ‘To the Lighthouse’ is a kind of literary impressionism. She uses fewer brushstrokes, daubs images instead of labouring them and repeats words, phrases, images, and events to give a sense of life’s essential messiness. It’s form but without formality, without the scaffolding.

‘Mrs Dalloway’ is the triumph of this method of ‘one thing opening out of another’ and in that respect it is and it isn’t a novel. Yes, there’s a plot but it’s a thin one: Clarissa Dalloway prepares for and hosts a party at her home. The subplots, such as they are, spiral out from her – they are to do with people she knows, meets or simply shares space with. So there is the immature fifty-three year old Peter Walsh, still chasing pretty girls; the stolid but dependable Richard Dalloway doing his best; the Dalloway’s daughter who’s the object of an uninvited infatuation; and the sad story of suicidal Septimus and his Italian wife Rezia, a story that’s only loosely threaded through the others as a result of location and co-incidence.

But between the two short statements which begin and end the book there is a ceaseless flow of images, thoughts, memories, guesses, interpretations and reconsiderations; a great torrent of pictures, sounds, colours and sensations; tastes and touches – the whole range of sensory perception tumbles out from Clarissa Dalloway, flows away from her, swirls around her, back into her and away again, ultimately to end with her in full focus.

There’s no pause, no let-up; it’s unbroken even by chapters. Not even poor Septimus who, leaping to his death from a window, could have provided a punctuation mark in the novel, a full stop - not even he does much more than break the surface of the flow that eddies around him.

A vision that begins in the Dalloways’ Westminster house then travels around central London, moving into Victoria Street, Regent’s Park, Piccadilly, Marylebone and Harley Street, constantly shifting point of view from character to character as their lives, like the streets, intersect. London is a harbour, filled with boats that bob and bump into each other before surging away. Then again it’s a body of water, like the Serpentine, snaking around itself. Repetition of snatches of memory or phrases gives the sense of ebb and flow while rooting episodes (Peter’s youthful love and loss of Clarissa, Sally Seton’s naked run from the bathroom, Rezia and her sisters making hats) and emotions (Peter’s sense of inferiority and injustice, Rezia’s unhappiness) in the memory, expanding them slightly each time.

What images to pick out of the profusion? The vagrant woman, standing in the gutter, singing with one hand outstretched; the aeroplane writing advertising slogans in the sky; nurses; children playing in the park; Big Ben marking the “irrevocable” passing of time; the “splendid morning like a pulse of a perfect heart”?

I find this one of the most memorable: the soul is described as

our self who fish-like inhabits deep sees and plies among obscurities, threading her way between the boles of giant weeds, over sun-flickered spaces and on and on into the gloom, cold, deep inscrutable

It’s an image that draws me up short every time, picturing the invisible secret part of ourselves as a slimy fish at the bottom of very deep waters. It makes the soul seem sunken, gloomy, and non-human; after all what could be less human than a fish?

‘They all sat separate’

‘Mrs Dalloway’ with its chapterless flow of incident and imagery and its dizzying leaps from perspective to perspective, feels different to most novels. It’s an epic poem in prose. In contrast, ‘To the Lighthouse’ with chapters and country-house setting looks and feels more like the conventional novel form of ‘Night and Day’. That’s misleading, however. The leaps of perspective are still there, but in this book the points of view are more filtered, the characters are more dimly perceived, like fire in the mist, crepuscular.

You can see the technique at work best in the dinner party chapter. In it Virginia Woolf is conductor, making her symphony work as much as Mrs Ramsay has to conduct her own symphony from a large, formal dinner. Everything about it is constantly shifting: moods, perceptions and opinions.

Like a concert, the Ramsays’ dinner party begins with discordant tuning up: Mrs Ramsay thinks, “What have I done with my life?” Her husband appears unattractive; the room is shabby; nobody is talking.

Nothing seems to have merged. They all sat separate. And the whole of the effort of merging and flowing and creating rested on her.

Realising that nobody else will make the effort to make the dinner work, she rallies herself and like a sailor who wearily sets off to sea, she sets off to make the party succeed. And because this is polite English upper class society, she has to do it all through code, through subterfuge. So, superficial conversation acquires deep significance: to voyage or not to voyage to the lighthouse; is letter writing worthwhile or a waste of time; an acquaintance is building a billiard room. None of the conversation reflects what anybody is really thinking or feeling and those inner thoughts are all about doubts, uncertainty, dislike, caring or not caring.

All of them bending themselves to listen thought, ‘Pray heaven that the inside of my mind may not be exposed,’ for each other thought, ‘The others are feeling this. They are outraged and indignant with the government about the fishermen. Whereas I feel nothing at all.

The whole conversation is struggling until Lily Briscoe, whose dogged determination not to play the same game as Mrs Ramsay fails her and she asks a polite question to enable another guest to talk. It’s a move that frees up the flow of conversation but is insincere and Lily reflects ruefully “she would never know him. He would never know her.”

Like ‘Mrs Dalloway’, the dinner continues to shift through a kaleidoscope of conversations and moods from views of all people involved before drifting lightly to an end as the increasingly erratic Mr Ramsay sings snatches of a folk song and they separate. It’s already the past.

A ‘thin strip of pavement over an abyss’

Skilful as it is, what’s the purpose of Virginia Woolf’s spectacular style and what’s more, why should we care about the clash of feelings in the minds of privileged people trying to make sense of what they’re really saying to each other?

She once wrote that “life without illusion is a ghastly affair” and that’s part of the key to understanding her. Despite being able to look unflinchingly at motives and the often brutal reality of life, she’s willing to embrace a certain degree of illusion to give it some shape, some semblance of order.

It’s a survival technique for those whom the worst dangers of life are removed: take away poverty and physical danger and the other problems of modern western life emerge: depression, mental illness, pressure to conform. Take away the servants and outmoded conventions and it’s our world too.

Virginia Woolf struggled herself with mental illness all her life and eventually succumbed to it. Even at her happiest she felt that life was like a “thin strip of pavement over an abyss”, an image from her diaries that repeatedly appears in her writing. What happens when you fall off that thin strip is truly terrible. It’s what happens to Septimus in ‘Mrs Dalloway” and Woolf’s depiction of his hallucinations, hauntings and hatred of humanity is terrifying. She knew it first hand.

And so ultimately despite the cynicism she credits her characters with about the society they inhabit, about the sacrifices they need to make (marriage, politeness, career), Woolf’s work is about trying to make sense of the clash between extreme feelings and constraints. Sometimes that leads to a coldness evident in the characters of hers who are most successful at making this kind of life work, like Clarissa Dalloway and Mrs Ramsay. But she celebrates them for making those choices and keeping the abyss at bay for at least a while.

It is Clarissa, he said.

For there she was.

As a final statement it’s unequivocal and an affirmation of existence that needs no embellishment.

Because here’s the real surprise: despite all the fear, the cynicism, the cold-eyed self-awareness and brutal examination of the motives of others; despite even the bleak tragedy of her own eventual suicide, Virginia Woolf was an optimist.

It pulses throughout every word and the rich profusion of images; the tumble of stories and criss-crossing lives in ‘Mrs Dalloway’. You can hear it in that surprisingly playful voice in that crackly old recording. That strip of pavement over the abyss is worth clinging onto. Virginia Woolf, like Clarissa Dalloway, is misunderstood:

They thought … that she enjoyed imposing herself; liked to have famous people about her; great names… And both were quite wrong. What she liked simply was life.