This is from 2008 and was written for the now-defunct magazine ‘the Raconteur’ which eventually grew into Wales Arts Review.

I was exactly twenty years old when I began reading Joseph Conrad. I know this peculiar fact because when my friends had asked me what birthday presents I wanted, I’d said to all of them, ‘Conrad.’ They obliged and into my life came the Rover, Heart of Darkness, The Secret Sharer, Lord Jim and a number of others. I still have those dog-eared paperbacks, all inscribed by old friends and I’ve added many more since then.

Now that Conrad has been with me half my life it’s easy to see what the attraction was then. A lot of his fiction is the work of a young man and filled with the sort of themes and dreams that bother young men and make them restless.

His heroes are seething with ambition to prove themselves, mixed with uncertainty about their ability to achieve just that. They’re single-minded, easily obsessed and just as easily betrayed, baffled and buffeted by an unsympathetic natural world.

Powerful as all that is though, it doesn’t explain why the works of this Polish merchant seaman, writing after his ocean-going career came to an end still captivate me after twenty years.

That they do is down to the rich profundity he began to mine by telling those stories inspired by his youth and the depths he uncovers in his later works. They aren’t light-hearted and rarely conclude happily but they burrow deep and they haunt you long afterwards.

In truth there are many different Conrads: the retired sea-dog spinning yarns of adventure in exotic locations; the chronicler of colonialism and its impact on those caught up in the enterprise of empire; the moralist judging his characters’ failings with acerbic severity.

If you haven’t read anything by him may I suggest his three finest books: Nostromo, The Secret Agent and Heart of Darkness.

I hope you’ll agree with me that, first and foremost, he’s a stylist of breathtaking skill. If you’ve never read Nostromo, nothing can prepare you for the apparently erratic and bewildering pace with which this story of a South American revolution unravels. It’s a masterpiece of time shifting which makes edgy contemporary film makers appear hopelessly conservative. You will be baffled, you will lose your bearings, but you will emerge with the sensation of having inhabited the fictional Sulacoa and really known the flawed, isolated people who map out their lives there.

Even as a twenty year old, reading Conrad for the first time, I was overcome by the pure poetry of his writing. His good friend Ford Madox Ford once suggested that some of his descriptive stretches could easily be chopped up into lines of iambic pentameter. And still now, reading Conrad takes a long time. That’s because whole passages stop you short and demand to be re-read there and then.

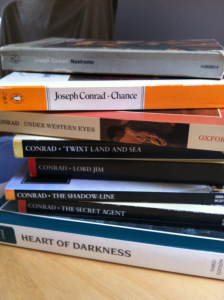

Take Heart of Darkness with its hazy, indistinct and adjectival hypnotism. Its tropical, greenhouse gas-filled atmosphere is heavy with symbolism, fuzzy of focus, and summed up in this, one of the earliest paragraphs:

In the offing the sea and the sky were welded together without a joint, and in the luminous space the tanned sails of the barges drifting up with the tide seemed to stand still in red clusters of canvas sharply peaked, with gleams of varnished spirits. A haze rested on the low shores that ran out to sea in vanishing flatness. The air was dark above Gravesend, and further back still seemed condensed into a mournful gloom, brooding motionless over the biggest, and the greatest, town on earth.

Sea and sky merge into one formless, hazy, luminous space in which moving things appear to be still, solid things appear  only to vanish again and the very air seems to solidify into mournful gloom. Later the sky is ‘gauzy’ and the object of the journey: the much spoken of Mr. Kurtz is ‘long, pale, indistinct like a vapour exhaled by the earth … misty and silent.’ So much for the Heart of Darkness – there’s nothing really there.

only to vanish again and the very air seems to solidify into mournful gloom. Later the sky is ‘gauzy’ and the object of the journey: the much spoken of Mr. Kurtz is ‘long, pale, indistinct like a vapour exhaled by the earth … misty and silent.’ So much for the Heart of Darkness – there’s nothing really there.

This blurred vision matches exactly what the narrator, Marlow, tells us about where to find meaning, ‘not inside like a kernel, but outside, enveloping the tale like ‘one of those misty haloes that sometimes are made visible by the spectral illumination of moonshine.’

You can spend a great deal of head-aching time trying to work out what this means if you want. I wouldn’t. The ‘misty halo’ business is really only there to add to the blurry – dare I say trippy – sense that the tale takes place in a fugue state of altered consciousness. Even so there is, ironically, a kernel of truth in what Marlow says and it’s worth paying attention to, because in Conrad, the truth very often is actually on the outside.

As I said, the atmosphere is heavy laden with meaning; significance clings to things, condenses and drips from what’s being described. Marlow watches two company officials who, walking in the low sun,

seemed to be tugging painfully uphill their two ridiculous shadows of unequal length that trailed behind them.

Their shadows, simple visual realities echo with the deeper failures of the men and the company they represent. These shadows are burdened because the men are burdened with weights that are unequal and ridiculous.

I’ve already made the comparison with filmmaking and Conrad is a master of direction looping effortlessly between speech, reported speech, inner thoughts and external images. In one episode in The Secret Agent, the frustrated and compromised Assistant Commissioner of Police seeks political permission to take matters into his own hands. Standing before the ‘big and rustic presence’ of the Home Secretary, the policeman – an intimidating presence in a previous chapter – now takes on ‘the frail slenderness of a reed addressing an oak.’ As he recounts the case, our attention is distracted towards a massive clock on a grand mantelpiece, ticking its way through seven minutes.

https://www.francismosley.com/index.html

Incidentally whilst we’re in Conrad’s Westminster, those who think of him as somehow otherworldly, austere and frankly humourless, should spend some time in the company of the Home Secretary’s youthful and enthusiastic Private Secretary (unpaid). His dedication to the boss’ wellbeing and absorption in his political battle over the Nationalisation of Fisheries is acutely observed, as is his nickname – Toodles – and his Bertie Wooster-ish shock that a fellow club member might not be a Gentleman ambassador but actually a foreign agent provocateur.

In my experience, the descendents of Toodles still populate the offices of Westminster. They tend to be paid these days, though not much. They continue to be young, with ‘symmetrically arranged hair’ and useful family connections. I’ve even seen ‘great personages’ leaning on their arms. And it’s worth noting that Assistant Commissioners of Police still find themselves in trouble over clashes between public good and private motives, particularly when it comes to anti-terrorism operations.

In fact, don’t expect any motives in Conrad to go unexamined, particularly those personal motives that affect public affairs.

Let me stay with that conflicted Assistant Commissioner. He finds himself undermining his highly respected Chief Inspector because of a tangle of motives, set out for us in all their compromising banality and naked self-interest. The reasons he resists attempts to pin the blame for the story’s central bombing outrage on an obese and ineffectual theoretical anarchist is not because he knows the man is innocent but because that anarchist’s half-baked philosophy is lapped up by society friends of his wife, friends who enable him not to feel so alienated from his wife’s social circle. The good opinion of one society hostess is particularly important to the Assistant Commissioner and when the thought distils itself in his mind that ‘she will never forgive me’, in that moment, the ‘frankness’ and ‘distaste’ of his motives become clear to himself because, skilled in unmasking others’ motives, he’s incapable of deluding himself. Simultaneously he acknowledges that he’s bored with his desk job, bored with city life, resentful of the old departmental hands and ill at ease in the society of his wife’s friends. The end result of this simmering pot of motives is success of sorts: the case is solved, the culprit uncovered, the Agent Provocateur warned off and the Home Secretary reassured. But the motives are entirely personal and not at all glorious. Unmasking motives is a good skill to have in life; Conrad has it in spades.

I can’t deny that Conrad’s vision is bleak. There’s no getting around the fact that there’s an immense and intense pessimism at the hard of his best work.

The reason for that pessimism lies in Conrad’s unflinching willingness to face the truth and to face reality. Motives are laid bare; treacheries, lies and failures are uncovered. And perhaps the most brutal truth that underlies all his fiction is the truth of ultimate loneliness.

In Nostromo, the brilliant and sophisticated journalist, Martin Decoud, habitué of Parisian salons and ironic observer turned unlikely revolutionary, abandoned on an island discovers the most appalling lack of self-sufficiency. Utterly alone for the first time in his life, he begins to

doubt… his own individuality. It had merged into the world of cloud and water, of natural forces and forms of nature.

After his inevitable suicide, when his body falls into the sea, he is literally and figuratively ‘swallowed up in the immense indifference of things.’

I can’t think of a better illustration of Conrad’s overwhelming pessimism than Decoud’s end, massive in its tragedy to the man, his lover and friends, but insignificant to the world.

For all its vast canvas of capitalism, conquest and revolution, Nostromo is essentially about private loneliness. Even the adored Emilia Gould is ultimately alone. As readers, we are allowed to know her doubts, despair and distress but only the peculiar doctor comes close to any sense of confidence with her. Something she realises with a shudder:

And it came into her mind, too, that no one would ever ask her with solicitude what she was thinking of.

This failure or inability to communicate, which F.R Leavis called ‘moral insulation’ is nowhere clearer than in the extraordinary confrontational scene between Verloc and his wife Winnie in the Secret Agent. While their daily domestic lives run smoothly parallel, neither is aware of the other’s secret life. Winnie has no inkling that her husband is a secret agent infiltrating and informing on anarchists that she supposes to be his friends. At the same time, Verloc has never wondered why an attractive young woman should choose an older, overweight and frankly seedy husband. It’s never occurred to him that marrying him was a means to provide stability for her mother and vulnerable brother. Their inner lives have remained insulated from each other; they’re both Secret Agents.

In this case knowledge doesn’t bring freedom, only cataclysm. Winnie’s brother has been killed in a failed bombing outrage cooked up by Verloc. The chasm of unknowing that lies between the two is vastest when they’re finally closest and Verloc is, for the first time, being honest. The price of opening his wife’s eyes? A carving knife between the ribs.

If we’re to avoid grim fates by carving knives or suicide on a desert island, what does Conrad believe guards against this ultimate loneliness?

Action.

In our activity alone do we find the sustaining illusion of an independent existence.

Does that cheer you up? If not try this:

Action is consolatory. It is the enemy of thought and the friend of flattering illusions. Only in the conduct of our action can we find the sense of mastery over the Fates.

And Nostromo is a whirlwind of frantic action: there is coup and countercoup, fighting, running, swimming, racing across mountains, audacious escape and superhuman endeavour. In the Secret Agent, our friend the Assistant Commissioner, chained to his desk and resentful of his job, staff and wife, finds release and satisfaction in walking out of his office, disguising himself and doing the job of detection himself.

But there’s a problem with action – if it’s consolatory, it’s also illusory. In Nostromo, the solitary Decoud

lost all belief in the reality of his action past and to come.

In other words, once we lose faith in our ability to affect our lives, then we lose faith in our own identity. It’s what the character Dr Monygham understands as

the crushing, paralyzing sense of human littleness, which is what really defeats a man struggling with natural forces, alone, far from the eyes of his fellows.

I don’t want to leave you with a sense of gloom and despair, though you need to be able to navigate those waters if you want to enjoy Conrad. I promise you there is optimism there. Of sorts. The unlikeable and unliked Dr. Monygham, haunted by personal collapse in the torture chamber finds awakened within him a renewed sense of self-respect that is ‘marked inwardly’ by the fading of nightmares. Love and decency have helped him limp towards this almost-redemption.

And there are flashes of humour, even in the grimmest of contexts. In Heart of Darkness, Marlow describes the effect of rotten hippo-meat brought on board by some of the native crew:

You can’t breathe dead hippo waking, sleeping and eating, and at the same time keep your precarious grip on existence.

As a motto for a successful life, I can’t improve on that.

I did my honors thesis on Conrad, concentrating on Lord Jim, so I got to spend my senior year at university reading as much Conrad as I could. I’ve NEVER forgotten reading Decoud’s end in the darkness of existential despair. Nothing compares! But then you read the Nigger of the Narcissus with its sea storm descriptions, or the time-stopping explosion in The Secret Agent, and you realize that Conrad could not write except with genius. Great review!

Thankyou so much. I also like the way that, just when you think you have a handle on Conrad, he surprises you. I recently read the story ‘The Black Mate’ and was delighted when the usual Conrad taciturnity in the central character turned out to be a disguise for a gleeful con trick!

I’m not familiar with that story. I’ll have to read it. Thanks!